By Barbara White Stack

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

January 31, 1997

Last year, a divorce Allegheny County couple asked a family court judge to decide where their two boys should play soccer and where they should go for religion classes.

It was another instance in a long and inglorious history of divorced parents demanding that judges decide the most mundane custody issues, including what dentist the children should see, whether they should wear tennis shoes on cold days and exactly what time dad ought to pick them up on Friday.

Max Baer, administrative judge for the Family Division of Common Pleas Court, refused to decide the parents’ dispute, saying they should work it out themselves.

And starting next week, Baer’s court will institute a program that he hopes will greatly diminish these parental standoffs.

Baer will announce today that all couples with custody disputes – about 2,500 each year in Allegheny County – must attend classes and then meet with a mediator. Their children must also go to classes. The new requirements start Monday.

The ambitious new requirement will apply to everyone who goes to court with a custody problem – those seeking divorce, those already divorced and those never married.

The classes will be provided by Family Services of Western Pennsylvania, a nonprofit human services agency that has counseled divorcing parents for years. The classes will last four hours and be offered at six centers throughout Allegheny County.

The children’s class, called Sandcastles, was developed by Florida psychotherapist M. Gary Neuman for the Dade County family court. He has trained Family Services staff to teach it. Children will be separated into four age groups and urged to discuss their feelings about the divorce.

Within a few weeks after the classes, parents must meet for at least 2.5 hours with a mediator certified by the American Academy of Family Mediators.

At this meeting, they can decide for themselves such matters as who gets custody on which days, whether dad will pick up the kids at 5 p.m. or 6 p.m. on a Friday, and whether the children will keep their pediatrician or switch to a new one closer to where mom is now living.

These are the types of issues that divorcing parents too often asked judges to decide. Baer thinks that parents and their children are better off if the parents settle such matters on their own.

“If you seek court help with custody, this (class-mediation program) is the way we intend to help you. I believe this is more helpful than giving you a courtroom and a judge,” Baer said.

Baer is not just trying to reduce the backlog clogging the already busy family court schedule. He also is trying to diminish the long-lasting damage to children – the type described by Judith Wallerstein, author of the most extensive study done on the effects of divorce on children.

Wallerstein has found that children who fare the worst are those who become shuttlecocks in a battle between their parents.

Experts say the struggle often takes the form of vindictive comments passed to the children. Mom may say, “Find out who daddy is dating.” Dad may say, “Your mother is so stupid she sent you here in January without boots.”

Wallerstein discovered that children whose divorced parents use them in continuing fights have even more problems than children whose parents die. After a parent’s death, a child at least has some time to heal.

But, Baer said, battling parents don’t offer that opportunity.

Some courts around the nation, and a dozen or two in Pennsylvania, require counseling or education for divorcing parents. Some, including Dade County, require it for the children, too.

But few require all three components – parents’ and children’s’ classes, plus mediation.

Baer’s new program could cost a couple with two children $840. That includes the parents’ classes at $40 each and children’s classes at $30 each. And it figures on 7.5 hours of mediation at a cost of $200 for the first 2.5 hours and $100 every hour thereafter.

While only 2.5 hours of mediation are required, Baer said successful mediation often requires at least four to five hours more.

Indigent parents will not have to pay for the classes or the mediation.

The cost is significantly cheaper than paying two lawyers $100 an hour to go to court directly to settle custody disputes. Kenneth J. Horoho Jr., chairman of the family law section of the Allegheny County Bar Association, said he had seen parents pay $30,000 to resolve the issue of whether a child will attend private or public school.

Rather than fight over where a child will attend school, “I want my clients to spend $30,000 to determine the value of a closely held family business,” Horoho said.

Of all the issues in divorce, custody is best suited for mediation, he said.

“It is just a little bit easier to get to ‘yes’ when you are talking about your kids,” he said.

For those who can’t agree, the old process remains. If mediation is unsuccessful, parents will meet with a conciliator who recommends solutions. If parents still can’t agree, the conciliator can tell a judge what was suggested and how the parents responded. Then the judge will decide the matter.

Baer said the goal of the new program would be to keep parents from being trapped in an escalating cycle of bickering.

Judges can decide custody disputes, Baer said, but that often doesn’t end them. If just means there will be another dispute the following week, because the real problem wasn’t resolved.

That problem, Baer said, is the parents’ failure to find ways to cooperate for the sake of their children.

_________________________

Counseling goal: Even in divorce, parenting partnerships are forever

By Susan Puskar

Assistant Managing Editor, Post-Gazette

What’s it like to be a child caught in the turmoil of a bitter divorce?

Ask someone who knows.

“I remember having a panic attack on the airplane as we flew to our new home. ‘Where’s my daddy?’ I remember screaming. I knew that he had already left, but I didn’t know much more. That’s how things went at the time. Nobody really talked to us or told us what was happening. There was a lot of confusion.”

“My mother was so angry and bitter. She was so wrapped up in her own emotions and feelings she didn’t know how to help us.”

“My father? I think he looked to get remarried as soon as possible so he didn’t really have to deal with us. He had no relationships with his children really. He did have his duty, as he saw it. He sent the checks. But that was about it.”

The woman doing the talking, who was 4 when her parents divorced, is in her mid-30s now, lives in the South Hills and asked that her name not be used. She says her parents’ bad marriage and even worse divorce have colored her whole life.

She felt insecure and singled out as a child, and carried those feelings into adulthood. She was attracted to the man she married partly because he seemed to come from such a big, happy family – the kind she imagined everyone but her had.

But that family ideal still eludes her.

She is separated from her husband and, by unpleasant coincidence, has a 4-year-old son who is trying to navigate some of the same territory she trod as a child, albeit with a more-knowing guide.

Even though there were no custody disputes to settle in her parents’ divorce – it was the 1960s and courts almost always placed children with their mothers, no questions asked – she vividly remembered the anger and hostility that permeated everything, even years later.

They’re the same feelings she’s trying to confront and conquer in her own situation.

She has sought counseling for herself and her son, and communicates regularly on parenting issues with her husband, who has moved to another son but visits his son frequently. Even when they disagree, which can be often, they try to keep their skirmishes from jostling their relationship with their child.

“We even went through a period when communication was breaking down,” the woman explained. “But we pretty quickly recognized that wasn’t helping anything. We know we really have to work together for our son’s sake.”

One issue she and her husband are trying to resolve is that when he comes to town, he usually sees his son in what had been the family home. She thinks that’s prolonging their child’s pipe dream that his parents will live under one roof again instead of reinforcing the reality that they’re moving in separate directions. The parents are trying to work out another arrangement that will serve their child’s best interests.

That philosophy – that parenting partnerships are forever even if marriages aren’t – is at the heart of most divorce education and counseling programs.

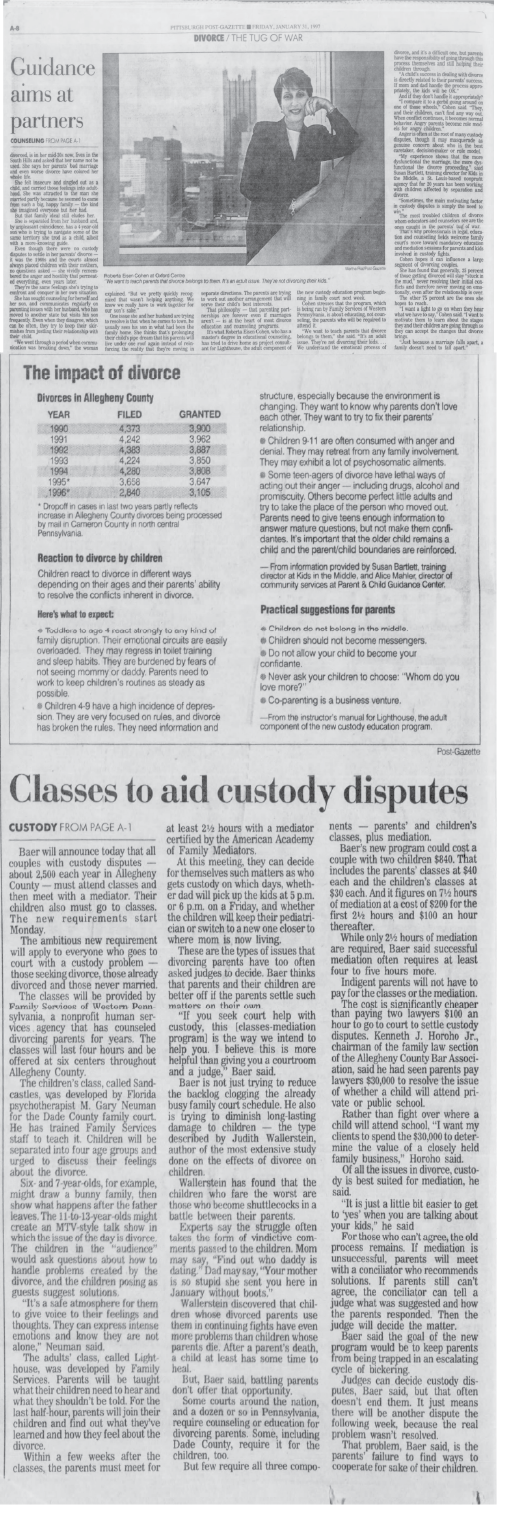

It’s what Roberta Eisen Cohen, who has a master’s degree in educational counseling, has tried to drive home as project consultant for Lighthouse, the adult component of the new education custody program beginning in family court next week.

Cohen stresses that the program, which is being run by Family Services of Western Pennsylvania, is about educating, not counseling, the parents who will be required to attend it.

“We want to teach parents that divorce belongs to them,” she said. “It’s an adult issue. They’re not divorcing their kids…We understand the emotional process of divorce, and it’s a difficult one, but parents have the responsibility of going through this process themselves and still helping their children through.

“A child’s success in dealing with divorce is directly related to their parents’ success. If mom and dad handle the process appropriately, the kids will be OK.”

And if they don’t handle it appropriately?

“I compare it to a gerbil going around on one of those wheels,” Cohen said. “They, and their children, can’t find a way out. When conflict continues, it becomes normal behavior. Angry parents become role models for angry children.”

Anger is often at the root of many custody disputes, though it may masquerade as genuine concern about who is the best caretaker, decision-maker or role model.

“My experience shows that the more dysfunctional the marriage, the more dysfunctional the divorce proceeding,” said Susan Bartlett, training director for Kids in the Middle, a St. Louis-based nonprofit agency that for 20 years has been working with children affected by separation and divorce.

“Sometimes the main motivating factor in custody disputes is simply the need to win.”

The most troubled children of divorce whom educators and counselors see are the ones caught in the parents’ tug of war.

That’s why professionals in legal, education, and counseling fields welcome family court’s move toward mandatory education and mediation sessions for parents and kids involved in custody fights.

Cohen hopes it can influence a large segment of divorcing couples.

She has found that generally, 25 percent of those getting divorced will stay “stuck in the mud,” never resolving their initial conflicts and therefore never moving on emotionally, even after their relationship is over.

The other 75 percent are the ones she hopes to reach.

“I want a light to go on when they hear what we have to say,” Cohen said. “I want to motivate them to learn about the stages they and their children are going through so they can accept the changes that divorce brings.

“Just because a marriage falls apart, a family doesn’t need to fall apart.”

Roberta Eisen Cohen at Oxford Centre “We want to teach parents that divorce belongs to them. It’s an adult issue. They’re not divorcing their kids.”

The Impact of Divorce

Divorces in Allegheny County

| YEAR | FILED | GRANTED |

| 1990 | 4,373 | 3,900 |

| 1991 | 4,242 | 3,962 |

| 1992 | 4,383 | 3,887 |

| 1993 | 4,224 | 3,850 |

| 1994 | 4,280 | 3,808 |

| 1995 | 3,658 | 3,647 |

| 1996 | 2,840 | 3,150 |

Dropoff in cases in last two years partly reflects increase in Allegheny County divorces being processed by mail in Cameron County in north central Pennsylvania.

Reaction to Divorce by Children

Children react to divorce in different ways depending on their ages and their parents’ ability to resolve conflicts inherent in the divorce.

Here’s What to Expect

- Toddlers to age 4 react strongly to any kind of family disruption. Their emotional circuits are easily overloaded. They may regress in toilet training and sleep habits. They are burdened by fears of not seeing mommy or daddy. Parents need to work to keep children’s routines as steady as possible.

- Children ages 4-9 have a high incidence of depression. They are very focused on rules, and divorce has broken the rules. They need information and structure, especially because the environment is changing. They want to know why parents don’t love each other. They want to try to fix their parents’ relationship.

- Children 9-11 are often consumed with anger and denial. They may retreat from any family involvement. They may exhibit a lot of psychosomatic ailments.

- Some teen-agers of divorce have lethal ways of acting out their anger – including drugs, alcohol and promiscuity. Others become little adults and try to take the place of the person who moved out. Parents need to give teens enough information to answer mature questions, but not make them confidantes. It’s more important that the older child remains a child and the parent/child boundaries are reinforced.

-From information provided by Susan Bartlett, training director at Kids in the Middle, and Alice Mahler, director of community services at Parent & Child Guidance Center.

Practical suggestions for parents

- Children do not belong in the middle.

- Children should not become messengers.

- Do not allow your child to become your confidante.

- Never ask your child to choose: “Whom do you love more?”

- Co-parenting is a business venture.

-From the instructor’s manual for Lighthouse, the adult component of the new custody education program.

View the full newspaper issue here.