Originally published in The Atlantic

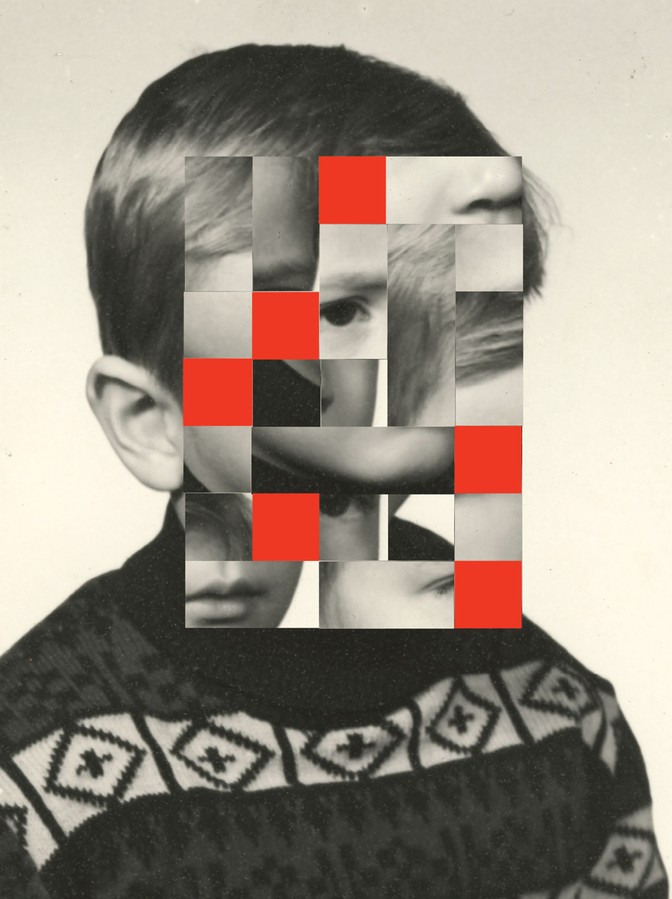

If life were fair, Benjamin and his sister, Olivia, would be spending this sunny July day fishing with their father and riding bikes around the small town in northern Ontario that they consider home. Instead, they are trapped in a townhouse in an ersatz Alpine village with a therapist and the mother they loathe, along with her partner and his two sons.

The day begins at 9 a.m., when a blond, middle-aged woman greets them by the unlit fireplace in the living room. She’s the therapist, and she tells the kids that while they’re here at the Family Bridges program, in a resort community two hours north of Toronto, they’ll watch some videos; learn to discuss problems as a family; and, of course, play a little miniature golf, shop in the village. Benjamin, a gangly 15-year-old, gazes out the sliding-glass doors, watching enviously as hikers ascend the gently sloping Blue Mountain. This isn’t a vacation, he thinks. This is an internment camp for brainwashing.

Benjamin and Olivia know what they know. Since their parents divorced in 2008, their mom has dragged their dad, Scott, to court and drained his bank account—he’s told them all about it. They’ve heard from him, too, that their mother suffers from depression, that she was once addicted to prescription drugs, that she cares less about them than she does about the students at the school where she teaches. All they want is to live with him full-time, but she won’t let them.

Later, the therapist asks Benjamin and Olivia to watch a video of some basketball players passing a ball back and forth. Count the passes, she instructs. The big reveal: The two siblings missed the person in a gorilla suit walking through the crowd. When you focus on one narrative, the therapist says, you miss important information. As the four-day program unfolds, she becomes more direct, urging the pair to rethink their assumptions. Perhaps their father is deliberately turning them against their mother, she says, introducing an idea called “parental alienation.” While their dad is painting their mother as narcissistic and selfish, maybe those traits actually belong to him?

Benjamin shakes his head. “We’re not falling for it.”

But then on the third day, when the therapist asks Benjamin to describe his relationship with his dad, he walks out to the patio, plunks down in a chair, and puts his head in his hands. Olivia follows, holding his hand as he cries. A breakthrough, the therapist assumes, a partial unraveling of the psychological ropes that bind them to their father.

Or not. “I miss Dad so much,” Benjamin says to himself. “When is this going to end?”

Benjamin and olivia found themselves at the Blue Mountain Resort because two weeks earlier, on June 20, 2014, an Ontario family-court judge had concluded that their father was waging an “all-out campaign to … alienate them from their mother,” a campaign so unrelenting that it qualified as psychological abuse. “This is one of the most egregious examples I have come across in my 23 years as a judge,” she observed, before issuing a dramatic ruling. She gave temporary sole custody of the children to Meredith, barred Scott from contacting them, and allowed Meredith to enroll them in treatment of her choosing. Meredith opted for the four days at Blue Mountain on the recommendation of the therapist running the intervention, who’d seen Meredith for several years in her individual practice.

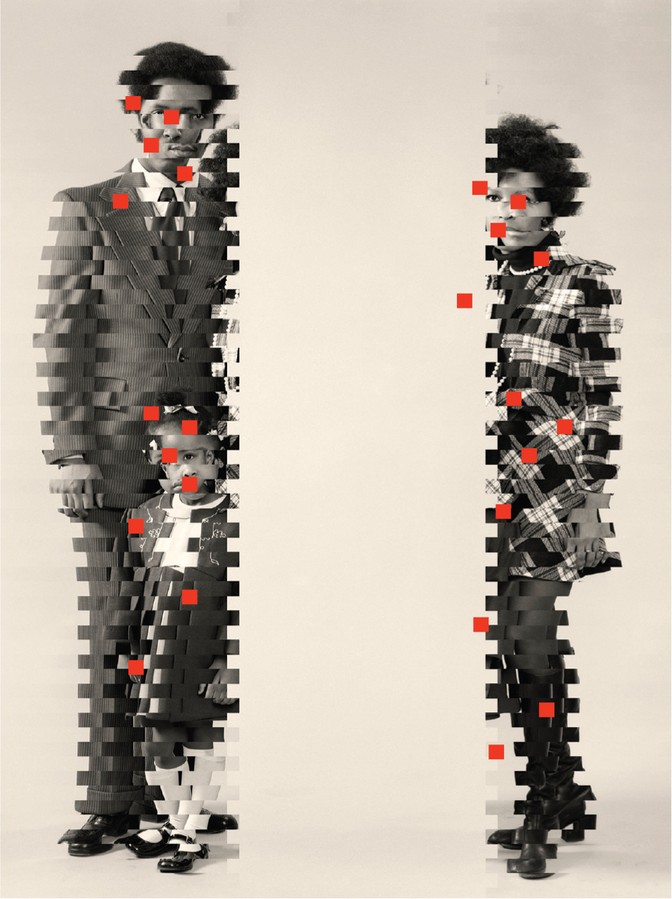

Parental alienation is the term of art for an extreme form of common behavior among divorced or divorcing couples. Even the most well-intentioned parents can occasionally find themselves denigrating their ex in front of the kids, or playing on their children’s affections to punish a former spouse. While most manage to check the temptation to use the children to lash out at an ex, a subset doesn’t. These people can’t or won’t stop trying to prejudice their children against their former partner.

Underlying this simple description of a recognizable phenomenon is a series of complicated questions that family courts struggle to settle. How much ugly invective, interference, and trash-talking counts as too much? How can you know for sure that children who are condemning a parent are distorting the truth? What if their mother or father actually is neglecting or abusing them? If a court manages to determine that a child has been wrongly turned against a parent, can anything be done to reverse the situation without causing additional damage? Olivia and Benjamin went more or less willingly to the Family Bridges weekend with their mother, but I watched a harrowing video of an adolescent boy being taken to a similar program. “Stop! Don’t touch me!” the child shrieks as two burly guys carry him out of the courthouse toward a waiting car. “Help me!” he yells, before the car door is slammed shut, muffling his screams.

More than 200 people filled the chilly ballroom of a DoubleTree hotel in Philadelphia in fall 2019, some typing furiously on their laptops, some hugging and whispering to one another, a few crying quietly as they listened to presentations at the Third International Conference of the Parental Alienation Study Group. In the past four decades, the diagnosis and treatment of parental alienation has grown into a small industry with a corps of therapists, academics, and attorneys. In one session after another, attendees heard about the tactics of alienators, such as forcing them to choose between Mom and Dad and so-called gatekeeping, or preventing children from seeing the other parent. Researchers described the signs of alienation, including a child waging “a campaign of denigration” against a parent, or spurning that parent for “absurd or frivolous reasons”—a rejection that eventually may extend to friends and relatives, even the family dog. Therapists laid out the psychological harm done to children in these situations (depression, trouble with later intimate relationships) while lawyers mapped out legal strategies to combat the problem, including the nuclear option: winning a change of custody and requiring the child to attend a reunification program with the disliked parent.

No one knows how common severe alienation is. The Vanderbilt University professor emeritus William Bernet, a psychiatrist who serves as an expert witness on behalf of people arguing that they’ve been victims of the phenomenon, estimates that there are 370,000 alienated children in the United States. But his figure is a rough extrapolation based on another rough figure, the annual number of high-conflict divorces. On Facebook, several parental-alienation groups have membership in the thousands. One night I joined a monthly conference call featuring alienation experts organized by a North Carolina grandmother; more than 1,000 people dialed in from around the world.

One girl, Kate, told me that after her dad moved out, her mother put a box of needles in the back seat of the car and warned that her father, a surgeon, planned to inject both of them with drugs. Kate was 7 years old. She loved her dad, but why would her mom lie to her? Eventually, she dreaded sleeping at her father’s house. “I would have terrible nightmares of my dad with drugs, trying to kill me,” she said. “I would practice holding my breath under the covers, in case I ever had to pretend to be dead.” As Kate entered her teens, she came to believe it was her mother, not her father, who presented the danger, and now, on court order, she lives with her dad.

After the parents of Rebecca separated when she was 12, her mother would beg her and her two younger siblings to refuse to visit their dad. “She’d say, ‘I don’t know what to do with myself when you guys are gone. I just sit in bed the whole time.’ ” When Rebecca complied, “my mom would be like, ‘I’m so proud of you. Let’s go shopping.’ ” Her mother, and her mother’s extended family, convinced the girl that her dad didn’t care about her, because he rarely took her to swim practice, helped her with homework, or gave her gifts. “And I was like, ‘Oh my God, yeah, he is such an asshole,’ ” she told me. On those rare occasions when Rebecca did visit her father, her mother directed her to take pictures of emails and legal documents, or read through his text messages. Within the space of a few months, she had turned against her father and was firmly on her mother’s side. After Rebecca’s parents spent upwards of $1 million on therapy and legal fees, a judge granted full custody to her dad, and Rebecca has reconciled with him.

Linda didn’t dispute these details. She told me that she had been driven to such lengths after her ex started privileging his new wife’s children over his own. “I am a female bear protecting two cubs, okay?” she said. “Let’s not mess with the den.” She didn’t encourage her children to have a warm relationship with their dad, she admitted, but she never intended to sever them from him. “I was fighting to wake him up. In my bull-in-the-china-shop way, I wanted to fix him as a parent. I can’t say I regret who I was.” After we finished the interview, Linda seemed giddy, as if she had successfully made her case.

It’s unclear why Scott, who’d been a stay-at-home dad before he and Meredith divorced, fought so hard to turn Olivia and Benjamin against their mother. No psychological records were introduced in court to illuminate his thinking. I agreed not to interview him because Meredith and her children feared that if I talked to him, he might follow through on threats he’d made to harm his ex-wife. In an affidavit filed with the family court, however, Scott maintained that “a vast majority of [Meredith’s] concerns are simply misstatements of events or exaggerations.”

About 12 years ago, with the divorce pending, Scott moved from the Toronto suburbs to his hometown a few hundred miles away. His children, then 7 and 9, joined him after school let out, where they say they spent the days playing outside and the evenings listening to their dad catalog their mom’s faults. His soliloquies ranged from the banal to the baroque. Their mom was a terrible cook—look how much weight they were losing! In college, she had befriended a man who murdered a young woman—Meredith was complicit and knew where the body was buried.

On the children’s first night back in Toronto after two months with their father, Meredith was rubbing Olivia’s back and telling her a bedtime story. Her daughter turned and looked up at her. “You’re not my real mother,” she said quietly. “This isn’t my real home. We want to go live with Dad.”

Meredith went numb, but assured herself that Scott’s hold on the children would attenuate once the children started school; after all, they stayed with him only during breaks. But she had not counted on the telephone. Every night at 6 o’clock sharp, he called. The kids would drop everything—dinner, playing with friends, homework, even their own birthday parties—to talk with their father for as long as two hours. “Part of it was him indoctrinating us,” Benjamin says. “Another part was him taking time out of Mom’s day, because she was only home in the evenings.”

Some of it might have been laughable to Meredith had the impact not been so painful. Scott coached the children to respond to every question with a mention of him. What do you want for breakfast? We want breakfast at Dad’s. What do you want for Christmas? We want to go to Dad’s. Why did Olivia hate Toronto so much? her mother asked once. “The traffic, the busy lifestyle!” the 8-year-old blurted.

Meredith tells me that she hid her miserable family life. She was ashamed, she says. What kind of parent has no relationship with her children? Often at lunch, her colleagues would describe their family vacations, and all the funny little things their kids said. Meredith would smile vaguely. I love my kids so much, she’d think. How is it that they despise me?

No one in the child-welfare world doubts that one parent can torpedo the other’s relationship with a son or daughter. But there is a huge debate over whether parental alienation is a diagnosable disorder like anxiety or depression, and if so, what kinds of interventions are appropriate. Part of the controversy springs from the concept’s tainted origins. In the 1980s, the child psychiatrist Richard Gardner defined the characteristics of what he called “parental-alienation syndrome,” and then traveled the country testifying in custody cases—almost always on behalf of men, many accused of sexual abuse. He argued that the men were innocent victims of “vengeful former wives” and “hysterical mothers.” A therapist must have a “thick skin and be able to tolerate the shrieks and claims” of abuse, Gardner went on. “It is therapeutic to say, ‘That didn’t happen! So let’s go and talk about real things, like your next visit with your father.’ ” Anyway, he claimed, “there is a bit of pedophilia in every one of us,” declaring that children are naturally sexual and may sometimes “seduce” an adult. His advocacy on behalf of men brought solace to fathers’-rights groups and sparked fury among feminists.

That question is central, and it’s shadowed by the fear that parents, most often men, could be using parental alienation to hide physical or sexual abuse. While alienation believers maintain that they’ve developed criteria to distinguish alienation from legitimate estrangement, the concepts aren’t precise or objective, says Joan Meier, a clinical-law professor and the director of the National Family Violence Law Center at the George Washington University Law School. “These are things that Gardner invented out of his head.” For instance, Meier told me, when a child insists that she’s telling the truth about her neglectful mother, that’s often taken as a sign that she’s lying—she doth protest too much. And alienation believers seem to discount the possibility that seemingly insignificant reasons for denouncing a parent might mask a darker issue, according to Meier. It’s easy for a boy to say he’s mad at his father for not letting him play in the softball game last weekend, Meier said. “It’s harder to talk about the time he made you take off your clothes and did weird things with you.”

That may be so in run-of-the-mill divorces, but therapy actually cements the hostility in alienation cases, argues Ashish Joshi, an attorney who represents unfavored parents. Joshi says he has witnessed variations of this scenario repeatedly: After months or years of manipulation, a boy truly believes that his father is evil, and he says during family therapy that he doesn’t want to visit his dad, because he’s mean and angry all the time. “What are you talking about?” the father responds. “I’m not mean.” At which point, the therapist intervenes and tells the father to stop protesting, to validate his child’s feelings. “And there never comes a time when the child says, ‘Okay. I’ve had my say. Thank you for listening. We can start afresh,’ ” Joshi contends. “The complaints never end.” And now a professional has reified them.

Ginger Gentile, a filmmaker who made a documentary called Erasing Family about young adults reuniting with a once-estranged parent, says the plodding nature of legal proceedings works in alienators’ favor. Even when the court ends up ruling that a child has been coerced into shunning one parent, if the kid still doesn’t want to have contact with that parent, “the judge is like: ‘What am I going to do? Put a 16-year-old in handcuffs?’ ” The custody battle ends only when the child ages out of the system at age 18, Gentile says, or the family experiences a dramatic crisis.

Such a crisis befell Meredith and her children in the spring of 2013. She discovered that Scott had arranged for his son, who was just finishing eighth grade, to go to a legal-aid office and change his residency from Toronto to his father’s town. (Scott claimed that it was the boy’s idea to hire a lawyer and leave Toronto.) When Meredith confronted Benjamin, he became unglued. “You fucking bitch!” Meredith recalls her son yelling. “You spoiled everything.” Around this time, Benjamin also wrote a short story, titled “Death’s Joy,” in which he described stabbing to death his mother and Eli, carving ruined on his own chest, and then drowning himself in Lake Ontario. Meredith sought an emergency court order to stop the children from visiting their father that summer, for fear she’d never get them back. The judge denied it, allowing the children to visit their dad in August, stating that “withholding them from dad’s life may be doing more harm than good in the long run.” He also said that the daily phone calls with Scott could continue.

Family bridges is the largest program of its kind in North America, but it operates outside the mainstream of psychological treatment. Until recently, it had no website; its four-day workshops take place in hotels and resorts, and they’re not cheap. The minimum fee is $20,000, but add to that room, board, transportation for family members—and, sometimes, the cost of hiring security personnel to escort resistant children—and the tab can run upwards of $30,000.

During their time at Blue Mountain, Benjamin and Olivia didn’t let on that they were having doubts about their dad. Olivia was stopped short by a movie called The Wave, about a schoolteacher who coaxes his students to join a fictional youth movement as an experiment to demonstrate how easy it is to fall under the thrall of cult leaders and dictators like Hitler. “Never in my life had I questioned what he said,” she tells me of her father. “It was terrifying, because if it’s all wrong, your life is flipped upside down.” For Benjamin, the dissonance began with the very video that Scott had shown them to try to discredit their mother: Welcome Back, Pluto. Watching it in the condo, Benjamin thought, Wait, that’s what Dad does with us. “It just slowly unraveled from there,” he says.

Family Bridges connected me with seven other families who, like Meredith and her kids, swore that nothing—no amount of love, reasoning, or punishment—came close to repairing the rupture until they attended the workshops. One dad compared it to treating cancer. “You know that chemotherapy is going to make their hair fall out. You know that they’re going to throw up violently,” he told me. “But you still do it, because you love your baby.” He’d reconciled with his daughter, who is in college and flourishing.

Although his study was peer-reviewed, it has the same kinds of limits as much of the alienation research. Warshak is not a neutral observer, having once participated in Family Bridges workshops as a psychologist. And there was no follow-up to see if the reconciliation endured beyond the hotel parking lot, nor any effort to tease out whether the kids could have been lying. “Are we really to believe that spending four days in a camp is going to dramatically change one’s cognitions, one’s idea of relationships?” asks the University of Toronto’s Saini.

Many of the “success” stories cited by reunification proponents contain a certain irony. When the programs seem to work, as often as not the children switch allegiances, cutting off the formerly favored parent and embracing the unfavored one. It’s all or nothing. Even the language the reunified children use—“abuse,” “poisoning”—slides off one parent and onto the other. Perhaps these children eventually settle into a loving relationship with both Mom and Dad, but as yet there are no studies suggesting as much.

Critics like Geffner also point out that Randy Rand, Family Bridges’ founder, is not a practicing psychologist. His license is inactive, a result of disciplinary action taken against him by the California Board of Psychology in 2009 based on two complaints. In one, the board concluded that Rand had had a contentious and unprofessional relationship with the mother in a high-conflict divorce, although he was supposed to be serving as an impartial adjudicator. In the second case, the board found that he’d given an expert opinion to a judge about a child he’d never personally evaluated.

Rand still participates in interventions, however, because he promotes Family Bridges as an “educational” rather than a “therapeutic” program. (He declined to comment for this article.) Geffner, not surprisingly, scoffs at this distinction—and calls reunification programs like Family Bridges “torture camp for kids.”

Gabriel and Mia would no doubt agree. In 2007, when they were 10 and 9, respectively, their parents’ marriage began to deteriorate, and the two gravitated toward their father. He was more laid-back, gentler, easier to live with, they thought, and not only did he never denigrate their mom, he always insisted they stay with her during her parenting times, no matter how the siblings protested.

When they arrived at the hotel outside San Francisco, Gabriel and his sister felt like “cornered animals,” he recalls. “You just tore us away from our home, to do this program that you claim is going to fix our relationship with our mom, at the same time as stripping us away from Dad for three months. You can imagine how receptive we were to that idea.” The psychologists tried to steer them to the conclusion that they’d been brainwashed, Gabriel tells me, and he and his sister “literally laughed in their faces.” When defiance failed, Mia suggested they change tack, suspecting that the best way to get back home would be to tell the Family Bridges people what they wanted to hear. “I told Gabriel: ‘Just fake it ’til you make it,’ ” Mia says. “The minute we left, we were like, ‘Mother, don’t speak to us.’ My God, I hated her so much.”

His mother, a physician, sees it differently. Were it not for Family Bridges, she says, she would not have the “robust bond” she has with her son. As for Mia? “Like everything in medicine, the treatment doesn’t work in 100 percent of cases.”

In addition to interviewing Mia and Gabriel, I read a first-person account by a girl who said she’d grown suicidal and cut herself when she was taken to a Family Bridges workshop at age 15; she claimed that the psychologists had threatened to ship her off to a psychiatric hospital. A young woman told me that her little sister had suffered panic attacks during the workshop; when the older girl challenged the Family Bridges therapists, they kept saying the girls would need “extra help,” which she understood to mean being sent to a wilderness camp for juvenile offenders. A teenage boy wrote that he is “still emotionally damaged from the program,” and that he “has difficulty connecting to others because I feel I can’t trust anyone.” None of these children has a relationship with the parent who brought them to the program.

Olivia and benjamin have not seen or spoken with their father in more than six years. Olivia, now in her second year of college double-majoring in gender studies and sociology, says she doesn’t miss him: “He was abusive. He was poisoning us. Why would I want to talk to him?” We are sitting on Meredith’s porch on a clear summer day, a light breeze stirring the trees. Olivia, who has long, dark hair and a raucous laugh, tells me that she struggles with anxiety and at times feels ill-equipped for adult life. Her dad’s omnipresence stole the mundane moments that define childhood, she says: painting her nails or going shopping with her mom, laughing all night at slumber parties. She dared not invest deeply in friendships, in school, in her Toronto family. “How can you, when you have this whisper in your ear all the time telling you it’s all meaningless, that nothing here matters?”

In a different way, Benjamin, too, lost himself. At 21, he’s in his third year of college, studying psychology. His eyes are cautious and he’s still very lean, swimming in his maroon T-shirt and blue jeans. His memories of his eighth- and ninth-grade years have for the most part disappeared, he says: He’s forgotten the attempt to move to northern Ontario, writing the story about suicide, and the fits of rage that Meredith says ended with her son curled in a fetal position on the floor. When he reviewed the court documents and his diaries before our interview, he says, “it was almost like reading a case study on a different person.”

For his part, Scott could have had a relationship with his children, if he would have engaged in counseling. Instead, he walked away. Now each member of the family has a restraining order against him. Meredith worries for her safety, recalling that he told his kids he would “hunt to the ends of the Earth” anyone who took his children away, to “make them pay.” Olivia and Benjamin just don’t want to deal with the emotional turmoil that ensues when he’s around. Therapists and lawyers say it’s common for alienating parents to disappear after losing custody fights: The children were only weapons aimed at the former spouse. The children were never the point.

This article appears in the December 2020 print edition with the headline “When a Child Is a Weapon.” It was published online on November 24, 2020.